How do I raise money for my startup?

One of the most critical challenges every startup venture confronts is raising capital. Whether you are personally funding (“bootstrapping”) a concept in a garage or preparing for a major venture capital infusion, the process involves choosing the right financial instrument, navigating complex securities laws, and managing long-term relationships with investors.

Raising money for a startup is often a marathon, not a sprint. It’s a structured process of moving from a raw idea to a scalable business by typically trading ownership (equity) for capital. For founders, understanding the roadmap, from the initial pitch to the final wire transfer, is essential to protecting their vision and their ownership. This article walks through each step of the process, ensuring your startup is legally protected and financially structured for growth.

Navigating the Capital Journey: An Overview of the Startup Fundraising Process

The fundraising process for a startup typically involves the following steps:

Step 1: Preparation and Governance.

Before engaging with investors, a startup must ensure its “house is in order.” This stage is less about the pitch and more about due diligence readiness. Investors will scrutinize your corporate structure, intellectual property assignments, and employment agreements. Ensure that all prior equity issuances (to founders and early advisors) are properly documented and prepare a data room with all material contracts, cap tables, and corporate records to streamline a potential investor’s review.

Step 2: Identifying the Right Instrument.

Not all capital is structured the same way. The choice of investment vehicle depends heavily on the company’s stage and the “maturity” of its valuation. Generally, as a company moves through different funding rounds, the complexity of the legal instruments increases.

Pre-Seed & Seed: Often the “friends and family” or early angel stage. The focus is on product development and initial market research.

Common Instruments: SAFEs or Convertible Notes. These allow for quick closing without the need for an immediate company valuation.

Series A: The first institutional round, usually led by venture capital firms. This stage is about scaling a proven business model.

Common Instrument: Priced Equity (Preferred Stock). This involves a formal valuation and more complex governance rights.

Series B & C: Growth-stage rounds designed for market expansion, acquisitions, and preparing for a potential exit.

Common Instrument: Preferred Stock with increasingly sophisticated terms regarding seniority and participation rights.

Step 3: Negotiating the Term Sheet.

Once an investor decides to commit, they will issue a Term Sheet. While largely non-binding, this document sets the “rules of engagement” for the entire deal. Key points of negotiation often include economic terms, control rights, and exit rights.

Step 4: Conducting Due Diligence and Preparing Documentation.

Once the Term Sheet is signed, the legal heavy lifting begins. The investor’s counsel will perform a deep dive into the company’s legal history. Simultaneously, both parties work to draft the definitive transaction documents (such as the Stock Purchase Agreement and Voting Agreement).

Step 5: Post-Closing Compliance.

After the documents are signed and the funds are wired, the process isn’t quite over. Startups must handle post-closing compliance matters, which include filing “Blue Sky” notices with state regulators and updating the company’s capitalization table to reflect the new stakeholders.

Step 1: Preparation and Governance

Before raising capital from external sources, you must establish a proper legal foundation. Investors conduct extensive due diligence, and a disorganized company can kill a deal before it starts. This foundational work is critical and, if done properly early, will dramatically streamline and accelerate future fundraising.

A. Entity Formation and Governance

Choice of Entity: While there are many entity types, the Delaware corporation remains the gold standard for venture-backed startups. Investors generally prefer corporations due to well-established case law, favorable tax treatment, and familiarity with Delaware corporate law. The alternative entity types (e.g., LLCs, partnerships, and S-corporations) carry pass-through tax liabilities that institutional investors want to avoid. If you formed as an LLC or other entity type, consult with legal counsel about converting prior to fundraising. Conversion should happen sooner rather than later, as migrating into a Delaware corporation after multiple rounds of founder equity has been issued and as the cap table becomes more complex will be much more costly and time-consuming.

Formation Documents: At formation, you should adopt a certificate of incorporation and bylaws that properly authorize equity issuances and contemplate future growth. These documents should be reviewed carefully to ensure they do not impose unexpected restrictions on fundraising that you’ll need to amend later.

Governance: Establish a formal board of directors from inception, even if it’s just you, and maintain board minutes documenting all significant decisions. This demonstrates professionalism to investors and creates a record that will be invaluable during diligence. As you bring on advisors or investors, formalize their roles and maintain proper board documentation.

B. Intellectual Property (IP) Protection

Your IP is likely your most valuable asset, and it is critical you ensure that the company actually owns it. This is one of the most common stumbling blocks we see: founders develop technology, but because they never formally assigned it to the company, the company doesn’t legally own it. This creates massive problems when investors arrive.

Assignment Agreements: Every employee, advisor, and consultant must sign a written agreement assigning their work product to the company. This agreement should include:

A provision that any work product created under the agreement is being commissioned as a “work-made-for-hire,” meaning the company owns all rights, title, and interest to such work. If your state restricts the broad assignment of employee-created intellectual property (e.g., California, Delaware, New York), the agreement should specifically assign work-related IP to the company.

An indemnity provision where the service provider agrees to defend and indemnify the company if their work infringes a third party’s IP.

A restriction on using open-source software (i.e., programs with publicly accessible source code) without written permission.

Copyright Registration: While copyright protection exists automatically upon creation, registering your copyrights with the U.S. Copyright Office provides additional protections (statutory damages, attorney fees recovery) if infringement occurs. Use proper copyright notices: “Copyright © [Year] [Company Name]” on important materials.

Trademarks and Domain Names: Register your company name, product names, and other marks as trademarks with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). While you can use marks without registration, registration provides stronger protection and clearer evidence of ownership. Secure relevant domain names early.

Digital Compliance: If you operate online, you must have Terms of Use and Privacy Policies that accurately reflect your data practices and comply with laws like the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which requires you to:

Designate an agent to receive notices of claimed infringement (register this with the U.S. Copyright Office).

Implement and publish a “notice and takedown” process in your terms of use.

Terminate access for repeat infringers.

C. Setting up the Cap Table

A capitalization table (or “cap table”) is a foundational document for any startup. It is a comprehensive ledger that tracks the equity ownership of the company and should include the following information:

The owner’s name and details of their ownership (e.g., type of security (common vs. preferred stock), number of shares, percentage ownership, and value of their ownership).

Any outstanding options and their vesting status.

Any convertible securities (e.g., SAFEs or convertible notes).

Fully diluted totals (what the cap table will look like if all warrants and options were exercised and all convertible securities converted).

Early in the process, founders should set aside an option pool, or a portion of equity (typically 10% to 20%) for future employees and advisors. Investors often require the pool to be created or expanded before they invest (i.e., pre-money), which dilutes the founders rather than the new investors. As noted above, the cap table must track vesting periods (usually, a 4-year term with a 1-year “cliff”) to show the difference between “granted” and “vested” shares.

All equity issuances must be properly documented with the following:

Stock Purchase Agreement - Grants the equity.

Board consent or resolution - Approves the grant.

Vesting Schedule - Details when the equity vests.

Section 83(b) Election - For founders and early service providers who receive stock that is subject to a vesting schedule or forfeiture provisions.

Typically, stock received as compensation is not taxed until it has vested. An 83(b) election allows the recipient to be taxed when the stock was granted. In the very early stages of a startup, the stock is usually worth nearly zero, so this election can result in massive tax savings.

Step 2: Identifying the Right Instrument

Startups have several paths to funding, each with distinct legal structures and long-term implications. Selecting the right instrument depends on the company’s maturity, the current valuation, and the speed at which the capital is needed.

A. Convertible Instruments (SAFEs & Convertible Notes)

For seed-stage companies that are too early to value or when you want to defer valuation negotiations, convertible instruments are the standard. These instruments defer the valuation negotiation until a later qualified financing (i.e., when the startup has raised a set amount in a future equity round), allowing rapid capital raising at the seed stage without the cost and complexity of a preferred stock round.

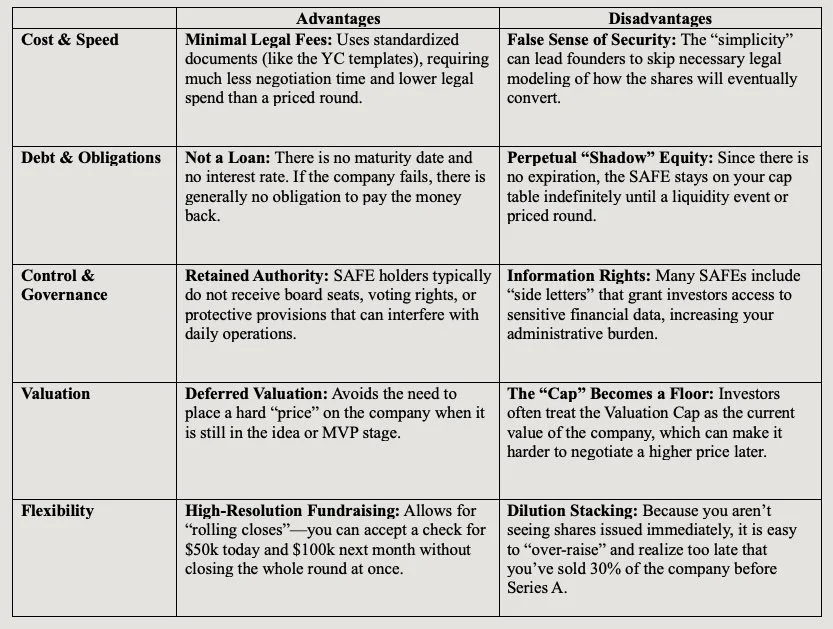

The choice between a SAFE and a convertible note is more than a technicality; it determines whether your initial capital is structured as a contractual right or a debt obligation. While both instruments defer the complex conversation of valuation until a future “priced round,” they carry different risks and legal burdens for the founders.

Simple Agreements for Future Equity (SAFEs)

Introduced by Y Combinator in 2013, SAFEs have become increasingly popular, particularly among accelerator-backed companies and in Silicon Valley.

A SAFE is a promise of future equity in exchange for a cash investment now. It is not a debt instrument, equity, or a contract to purchase equity. Like a convertible note, it converts into equity upon a qualified financing or corporate transaction. However, unlike notes, SAFEs:

Do not accrue interest: The investor receives no interest payments.

Have no maturity date: There is no obligation for the company to pay the money back if the qualified financing does not occur.

Key Terms:

Valuation Cap: The agreed upper limit on the company valuation used solely for converting the SAFE into shares. This effectively sets the highest price the investor will pay per share. If the next round is at a higher valuation than the cap, the investor converts at the lower-capped valuation and gets more equity for the same investment.

Discount Rate: A percentage reduction (typically 10% to 25%) off the price per share of the next priced round, rewarding early risk.

If the SAFE has both a cap and a discount, the investor usually uses whichever provides the more favorable (i.e., lower) share price.

Pre-Money vs. Post-Money: Determines if ownership is calculated before or after the new money comes in. Since 2018, post-money SAFEs have been the Y Combinator standard. These are generally more investor-friendly because the investor’s ownership is “locked in” and not diluted by other SAFEs being raised in the same round.

Pro-Rata/Participation Rights: Allow the investor to invest additional funds in future rounds to maintain their percentage of ownership. Usually, these are reserved for “Major Investors” (e.g., those putting in $100K or more) and granted via a separate side letter. Major Investors are also typically granted access to company financial information.

Most Favored Nation (MFN) Clause: Protects an early investor if you later issue a SAFE to someone else on better terms (e.g., a lower valuation cap), automatically upgrading their SAFE.

The Y Combinator Standard Form:

Y Combinator publishes standard SAFE forms that have become market-standard, available on their website. These forms come in variations depending on discount terms. The standardization of these forms means most investors and counsel are comfortable with minimal modifications, and experienced investors will often accept the standard form provisions (with the exception of negotiating the valuation cap and discount rate). This is a major advantage over convertible notes, which require more negotiation.

SAFE Financing: The Founder’s Perspective

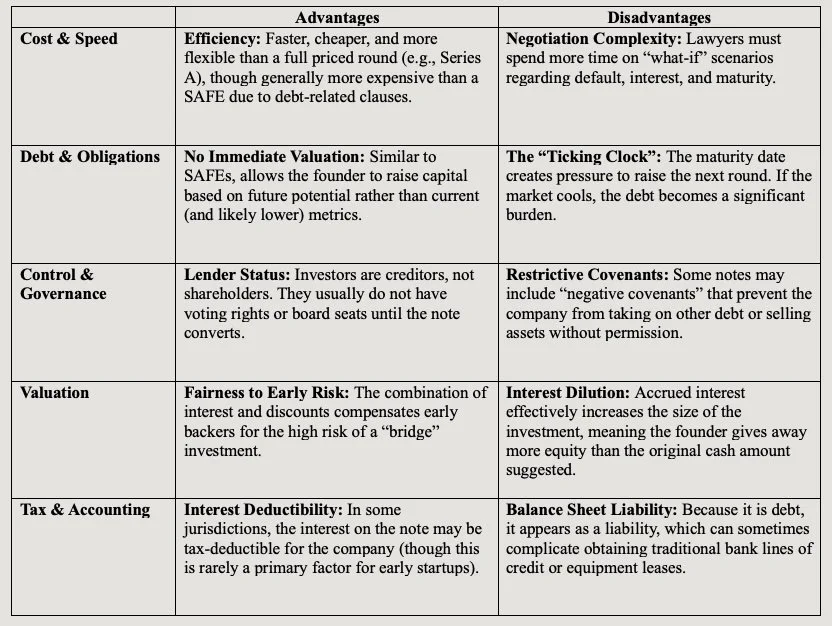

Convertible Notes

A convertible note is a debt instrument through which an investor lends money to your company and earns interest during the note’s lifetime. However, rather than repaying the note with cash at maturity, the note converts into equity upon a qualified financing, similar to the conversion of a SAFE.

While they serve a similar purpose to SAFEs by allowing a startup to delay a formal valuation, convertible notes are legally structured as loans. This means that they carry legal obligations that SAFEs do not. Convertible notes are often favored by more traditional angel investors or investors outside of major tech hubs who want the added protection of being a “creditor” rather than a mere “contract holder.”

Unlike the Y Combinator SAFE, convertible notes are less standardized. Notes often require more substantive legal drafting regarding default provisions, security interests (whether the loan is “secured” by company assets), and amendment rights.

Key Terms:

Principal Amount: The total investment amount.

Maturity Date: The date by which the note must either convert into equity or be repaid (usually 18-24 months from issuance). If a startup has not raised a priced round by this date, it may be forced into a “technical default,” requiring a negotiation for an extension.

Interest Rate: Unlike SAFEs, notes accrue interest (typically in the range of 4% to 8%)). This interest is rarely paid out in cash; instead, it “accrues” to the principal, meaning the investor receives more shares upon conversion.

Valuation Cap: Similar to SAFEs, the cap is an agreed-upon ceiling on the valuation at which the note converts. This ensures early investors are rewarded with a lower price per share than later investors if the company’s value increases significantly.

Discount Rate: Similar to SAFEs, the discount rate is a percentage discount (typically 10% to 25%) on the share price of the next round.

Like a SAFE, if the note has both a cap and a discount, the investor usually uses whichever provides the more favorable (lower) share price.

Conversion Triggers: Specific events that force the note to turn into stock, most commonly a qualified financing for a threshold amount.

Corporate Transaction/Change of Control: Terms that dictate what happens if the company is sold before the note converts. Usually, the investor receives a multiple of their investment (e.g., 1.5x or 2x) or converts to common stock at the cap to participate in the proceeds.

MFN Clause and Pro-Rata/Participation Rights: Same considerations as SAFEs.

Convertible Note Financing: The Founder’s Perspective

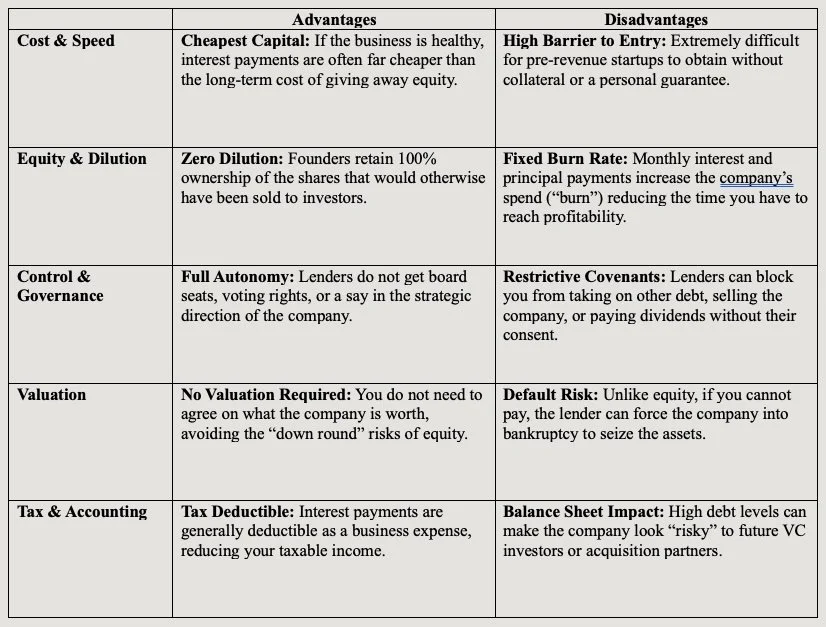

B. Traditional Debt

Debt financing involves borrowing funds with a promise to repay principal plus interest by a maturity date. Unlike SAFEs or convertible notes, traditional debt is not intended to convert into ownership. Debt is appropriate for companies with predictable cash flows or significant tangible assets. For early-stage startups, this is rarely the first source of capital unless the founders have high personal credit or the business has immediate, consistent revenue.

Traditional debt is governed by a Promissory Note and Security Agreement. These are heavily standardized by banks but are much more restrictive than startup-centric instruments. They include extensive “Events of Default” clauses that give the lender significant power if a single payment is missed or a covenant is breached.

Types of Debt Facilities:

Term Loans: A single draw of funds repaid over a set period (typically 4-7 years) via quarterly installments. These work well for one-time capital needs like acquiring equipment or funding an acquisition.

Revolving Credit Facilities: Similar to a business credit card; the borrower may borrow, repay, and re-borrow up to a pre-established limit. You pay interest only on the amount actually drawn. These are useful for working capital fluctuations and cash flow management.

Bridge Loans: Short-term loans (typically 6-12 months) providing temporary financing until permanent capital is secured (e.g., a bridge loan prior to a Series A to cover operating expenses).

Syndicated Loans: Larger loans arranged through a lead bank (administrative agent) that syndicates portions to other lenders. The agent manages payments, compliance, and amendments.

Mezzanine Debt: Subordinated to senior bank loans but ranking above equity in priority. Mezzanine lenders often include an “equity kicker”—warrant coverage or conversion features giving them potential equity upside. Mezzanine is used in later-stage companies as a bridge to equity.

Debt Financing: The Founder’s Perspective

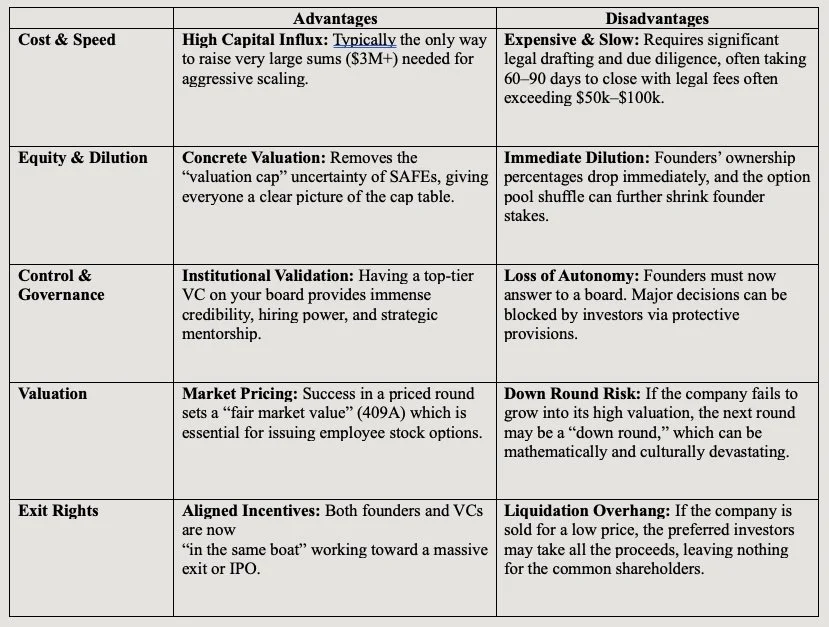

C. Priced Equity (Preferred Stock)

Once your company demonstrates meaningful traction—a working product, initial customers, recurring revenue, or other risk-reducing proof points—you may be ready for a formal equity round. Unlike SAFEs or convertible notes, which are “promises” of future equity, a priced round involves the actual sale of shares at a specific, negotiated price per share.

In these rounds, investors (typically venture capital firms) do not receive common stock like the founders. Instead, they receive preferred stock, which grants them specific rights, preferences, and privileges that sit senior to the founders’ shares. This means that once you issue preferred stock, the investors have a permanent seat at the table. A priced equity round represents a substantial commitment from institutional investors and should be undertaken only after careful strategic planning.

Key Terms:

Pre-Money vs. Post-Money Valuation: The “pre-money” valuation is the agreed-upon value of the company before the investment. The “post-money” valuation is the pre-money plus the cash invested. This determines the exact percentage of the company the investors will own.

Dividend Preference: Preferred shareholders may receive dividends before common shareholders, incentivizing the company to distribute profits. However, in practice, venture-backed companies rarely pay dividends, so this is often a theoretical provision.

Liquidation Preference: Upon company sale, liquidation, or merger, preferred shareholders receive their investment back (plus any accrued dividends) before common shareholders receive anything.

Non-Participation Preference (Founder-Friendly): Preferred shareholders only receive their investment back.

Participating Preference (Investor-Friendly): Preferred shareholders receive their investment back in full and then participate pro rata in the remaining proceeds.

Conversion Rights: Preferred stock is convertible into common stock, typically automatically upon an IPO or upon approval by a specified percentage of preferred shareholders. This gives investors an exit path if the company goes public.

Board Seats: Lead investors in a priced round almost always require a seat on the company’s board, shifting the company from founder-control to shared-governance. Board seats give investors direct input into strategy, hiring, spending, and potential exits.

Protective Provisions (Veto Rights): A list of corporate actions that the company cannot take without the express approval of the preferred shareholders (e.g., selling the company, changing the charter, or issuing more debt).

Anti-Dilution Protection: Protects investors if the company later raises money at a lower valuation (a “down round”) by adjusting the conversion ratio of their preferred stock.

The Option Pool Shuffle: Investors usually require the company to increase the employee option pool before the investment, which effectively lowers the pre-money valuation and places the dilution burden entirely on the founders.

Preferred Equity: The Founder’s Perspective

Step 3. Negotiating the Term Sheet

In a priced equity round, the term sheet is the blueprint for the entire transaction. While it is generally non-binding (except for clauses like confidentiality and exclusivity), it dictates the legal and economic framework of the company for years to come. The NVCA form term sheet is notably detailed compared to other term sheet templates, intentionally providing extensive guidance on market alternatives for nearly every provision.

In a priced round, there is typically only one term sheet for the entire round, which is almost always negotiated and signed between the company and the lead investor. The lead investor is the entity (usually a VC firm) putting in the largest portion of the capital (often 50% or more of the round). Because they have the most at stake, they do the “heavy lifting” of due diligence and negotiation. Once the founder and the lead investor sign the term sheet, the terms are generally considered set for the rest of the round.

The other investors in the round (often called “participating” or “syndicate” investors) usually do not get their own term sheet. Instead, they are invited to join the round on the exact same terms negotiated by the lead investor, subject to certain rights (e.g., board seats or information rights) granted to major investors or certain rights contained in a separate side letter between the company and a specific investor.

A. Key Terms

Negotiating a term sheet is a balancing act between the economics (how much the company is worth and who gets paid first) and control (who makes the decisions).

Economics: Valuation and Dilution

Pre-Money vs. Post-Money: Ensure that the parties understand which valuation is being discussed, as a misunderstanding can result in significant differences in the anticipated cap table.

The Option Pool Shuffle: Investors usually insist that the employee option pool be increased before the investment. This is a common negotiation point because the dilution comes out of the founders’ shares, effectively lowering your true pre-money valuation.

Liquidation Preference: This dictates the “payout order” in a sale.

A 1x Non-Participating Preferred preference is the most founder-friendly. This means investors get their money back or their share of the proceeds, but not both. This is the more founder-friendly option.

A 1x Participating Preferred preference allows the investor to receive their investment back, plus their share of the proceeds. This is also known as “double-dipping” and is the more investor-friendly option.

Higher Multiple Liquidation Preference: Some investors negotiate for 2x, 3x, or higher multiples on their liquidation preference. This is rare in Series A but more common in later rounds.

Capped Participation: This is a hybrid where participating investors receive their initial investment amount plus a pro-rata share of the proceeds, but the sum of all amounts received is limited to a certain total return cap (e.g., 2x or 3x the initial investment). Once the cap is reached, they no longer participate in the remaining distribution.

Seniority Structure: When a company has multiple funding rounds, the seniority structure dictates the payout order among different classes of preferred shareholders.

Pari Passu: All preferred shareholders across all funding rounds have equal priority and share proceeds proportionally if funds are insufficient to cover all preferences.

Standard: The latest investors (e.g., Series C) get paid in full before earlier investors (e.g., Series B, then Series A), who are then paid before common shareholders.

Tiered: This seniority approach is a hybrid of Pari Passu and Standard. Investors are put into tiers, and in each tier, payouts are distributed on a Pari Passu basis.

Vesting Acceleration: Acceleration clauses dictate what happens to unvested founder and employee stock when the company is sold in the future.

With a single-trigger clause, unvested stock accelerates and becomes fully vested immediately upon the sale of the company. However, this gives the buyer no incentive to keep the existing team.

Stock vests under a double-trigger clause if the company is acquired and the individual is terminated without cause by the new owner within a certain timeframe (e.g., 12 months). This approach is more common to align the incentives of the buyer and employees, but also provide protection for employees who are terminated shortly after the sale.

Control: Governance and Veto Rights

Board Composition: A common structure for a Series A is 2-2-1: two founder seats, two investor seats, and one independent seat agreed upon by both.

Protective Provisions: These are “veto rights” where the company cannot take certain actions (selling the company, changing the budget, hiring/firing the CEO) without consent from the lead investor or a particular class of stockholders.

Drag-Along Rights: These allow a majority of shareholders to force a minority of shareholders to join in the sale of the company, with the same terms. Founders should ensure the “threshold” for triggering this is not too low.

Investor Protections

Anti-Dilution: Most term sheets include “Broad-Based Weighted Average” anti-dilution. This protects investors if you raise money later at a lower valuation (a “down round”). This formula adjusts the investor’s conversion ratio based on the relative size of the prior round and the new lower-priced round.

Narrow-Based Anti-Dilution: More investor-friendly; calculates dilution using only preferred stock shares outstanding, not all shares. Results in greater adjustment to the investor’s conversion price.

Full Ratchet Anti-Dilution: Most investor-friendly; drops investor’s conversion price all the way to the new lower price, regardless of how many shares were sold at that price. If Series A investors paid $10/share but Series B came in at $5/share, ratchet protection adjusts Series A investors’ conversion price to $5/share. Founders hate ratchet but investors love it in down rounds.

Tag-Along Rights: These protect minority investors by ensuring they are not left behind if a founder sells their shares to a third party. Upon a sale of the founder’s stock, the investors will have the right to “tag along” and sell a proportionate amount of their own shares to the same buyer on the same terms.

Dividends: While rare in high-growth startups, some investors ask for “cumulative dividends.” Founders should push for “non-cumulative, when-and-if declared” dividends.

Registration Rights: These outline how an investor can force the company to register their shares with the SEC (demand rights) or to piggyback on company-initiated registrations (piggyback rights).

Information Rights: These typically include requirements to provide quarterly and annual financial statements, an annual budget, and sometimes “inspection rights” to visit the company’s offices.

B. Negotiation Tips for Founders

Leverage Market Standards: Venture capital has established norms and standard forms. If an investor asks for a 2x liquidation preference or a permanent board seat for a small investment, point to industry standards (like the NVCA templates) to push back. A law firm can provide data on what is “market” for your specific stage and region.

Focus on the Whole Deal: A high valuation with “dirty” terms (like high liquidation multiples or heavy veto rights) is often worse than a lower valuation with “clean” terms. Dirty terms can make your company uninvestable for future Series B or C rounds.

Watch the Exclusivity Period: Term sheets usually include a 30- to 45-day no-shop clause. Once you sign, you cannot talk to other investors. Ensure you are 100% committed to the lead investor before signing, as this effectively takes you off the market while they conduct final due diligence.

Step 4. Conducting Due Diligence and Preparing Documentation

A. The Due Diligence Process

Institutional investors conduct extensive due diligence before investing. The companies that raise capital most efficiently are those that prepare thoroughly in advance. Preparing and organizing a virtual data room (using Intralinks, Carta, or even a shared Box/Google Drive) will streamline an investor’s review, signal professionalism, and make the diligence process run much more efficiently. Documents in the data room should cover the following key areas:

Corporate Governance: Are your formation documents and corporate actions properly documented? Is the company in “good standing” in its state of incorporation?

Documents: Properly authorized and filed certificate of incorporation, properly adopted bylaws, board meetings properly documenting all significant actions, and corporate resolutions approving equity issuances.

Capitalization: Is your cap table accurate?

Documents: Proper documentation for all equity issuances, copies of 83(b) elections filed for restricted stock, documentation on the option pool, and any option grants issued with vesting schedules.

Intellectual Property: Does the company own all of the necessary IP?

Documents: Proprietary Information and Inventions Assignment Agreements (PIIAs) or similar assignment agreements for founders, employees and contractors. Open-source software usage is documented and compliant.

Financials and Tax: How is the company’s financial performance?

Documents: Audited or reviewed financial statements, detailed financial projections, cash flow analysis, bank statements, outstanding debts, key financial metrics, and tax filings.

Employment and Human Resources: Does the company have all necessary documentation relating to its employees?

Documents: Employment agreements, non-disclosure agreements, and verification that there are no pending labor disputes, misclassified independent contractors who should be employees, or handshake equity promises that are not reflected on the cap table.

Contracts: How is the company currently operating?

Documents: Customer contracts (redacted if necessary), vendor agreements, key partnerships, and lease agreements.

Legal & Compliance: Is the company complying with all relevant laws? Are there any ongoing disputes?

Documents: Litigation summary, regulatory compliance, insurance policies, and corporate compliance.

B. Preparing the Definitive Documentation

While diligence is ongoing, the lawyers will draft the five core documents that will govern the investment. Rather than drafting financing documents from scratch, the vast majority of institutional venture rounds leverage the NVCA Model Legal Documents, a standardized suite created by the National Venture Capital Association. Approximately 85% of Series A companies use NVCA forms for their equity financing rounds. These documents reflect current market practice and are familiar to virtually all institutional investors, counsel, and startup advisors.

Using NVCA forms provides several critical advantages:

Establish a common baseline that dramatically accelerates negotiation. Both parties understand the framework and can focus negotiations on economic terms (valuation, board seats, liquidation preferences) rather than bogging down in document structure.

Reduce legal costs substantially. Rather than counsel drafting custom documents from scratch, they begin with NVCA forms and make targeted modifications, reducing billable hours significantly.

Ensure that the documents reflect current law and practice. The NVCA Committee, composed of approximately 50 lawyers representing both VC firms and companies, continuously updates these forms to reflect current Delaware case law, legislative changes (like recent CFIUS rules), and evolving market practice. The most recent update in October 2025 incorporates mechanics for tranched financings (particularly common in life sciences), direct listing provisions reflecting market-standard IPO treatment, and updated provisions around officer liability and cash management obligations.

The core NVCA financing documents include:

Certificate of Incorporation (Charter): The only publicly filed NVCA document, this amends your company’s charter to create the new series of preferred stock (e.g., Series A Preferred) and defines its rights and privileges, including liquidation preferences (whether non-participating, participating, or capped), dividend rights, conversion mechanics, voting rights, and protective provisions giving preferred holders veto power over major actions.

Stock Purchase Agreement (SPA): The binding contract for the actual sale of shares. The SPA includes representations and warranties (what the company represents as true about its business, IP, financial condition, compliance, and legal status), conditions to closing (what must be satisfied before money exchanges hands), and closing mechanics (e.g., provisions addressing multiple closings and tranched closings, to accommodate simultaneous investor rounds and time- or milestone-based funding structures).

Notably, the updated NVCA SPA eliminated founder personal representations from the main body of the agreement, reflecting market practice where founders typically bear no personal liability to investors post-Series Seed unless receiving transaction proceeds or presenting heightened due diligence concerns.

Investors’ Rights Agreement (IRA): Governs the rights investors receive post-closing, including registration rights, information rights, and pro rata rights.

The updated IRA now mandates that companies deliver annual board-approved budgets and includes optional language requiring adoption of a cash management policy, reflecting institutional investor expectations for financial governance.

Voting Agreement: Formalizes how shareholders will vote on key matters, primarily board composition and major corporate transactions. This agreement specifies board size, seat allocation between common and preferred holders, the voting mechanics for board elections, and drag-along rights.

The 2025 updates clarify that board seat designation rights do not automatically transfer to assignees of shares, unless the parties explicitly agree otherwise.

Right of First Refusal and Co-Sale Agreement (ROFR): Restricts the ability of founders and employees to sell their own shares without first offering them to the company or the investors. If shares remain after investor elections, parties often have an “oversubscription” right to purchase more than their pro rata share. Additionally, if a founder sells shares to a third party, investors have tag-along rights allowing them to sell a proportional amount of their shares on the same terms, preventing scenarios where founders cash out while investors are locked in.

Beyond the core documents, NVCA offers additional supporting agreements:

Management Rights Letter (Side Letter): A supplementary agreement allowing major investors additional governance rights, such as the right to attend (but not vote at) board meetings, access to management, or direct communication channels with the CEO. These side letters are typically offered only to the lead investor or investors holding a minimum ownership percentage.

Indemnification Agreement: Addresses indemnification mechanics, particularly regarding what officers and directors are indemnified for and at whose expense. This clarifies D&O insurance obligations and personal liability caps.

Model Legal Opinion Template: Company counsel’s opinion that the company is validly existing, properly authorized, and capable of entering into the transaction.

Questionnaires for Director and Officer Suitability: Used to gather essential information for SEC filings and stock exchange compliance, typically when preparing for an IPO or annual proxy statements. These questionnaires collect data to ensure transparency, identify potential conflicts of interest, and confirm director qualifications.

Specialized Documents:

Model PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity) financing documents: For post-acquisition funding of public companies

Life-Science Confidential Disclosure Agreements: For industry-standard diligence processes for biotech and pharma companies

Using NVCA Forms: Market Terms and Flexibility

NVCA forms are the starting point, not a straitjacket. The documents include extensive footnotes and bracketed alternatives reflecting the range of market practice. For example, the liquidation preference section includes alternatives for non-participating (founder-friendly), participating (investor-friendly), and capped-participating (balanced) structures. The anti-dilution section offers both broad-based weighted-average (founder-friendly) and narrow-based (investor-friendly) calculations. Protective provisions can be narrowly tailored (only board hiring, budget spending, and business material changes) or expansively drafted (including any action requiring board approval). The point is that while NVCA forms establish a common baseline, they explicitly contemplate variation within market norms. Our counsel will work with you to select the appropriate provisions, fill in the critical brackets, and negotiate investor positions on contested terms.

C. Negotiating the Disclosure Schedules

The disclosure schedules are perhaps the most important legal protection for a founder. While the SPA says, “We have no lawsuits,” the disclosure schedules list all exceptions and potential issues (e.g., “Except for the small dispute with X vendor.”). By disclosing every potential issue (pending disputes, expired licenses, etc.), you shift the risk to the investor. On the other hand, if you fail to disclose a material issue and it causes a problem later, the investors may have a legal claim for a breach of the representations contained in the SPA, which can lead to significant personal liability for founders or a clawback of funds.

D. Closing the Round

Once the documents are finalized and the investor’s counsel has completed its diligence, the process moves to closing.

Closing Binder: Includes all documents and necessary consents for the investment.

Signature Packages: In the modern era, this is done via DocuSign or platforms like Carta.

Initial Board Meeting: The board formally approves the deal and the issuance of new shares.

Funding: The investor sends the funds (less any transaction fees that the startup has agreed to pay out of the proceeds).

Step 5: Post-Closing Compliance

Every time a company issues stock, options, notes, or any other security, it generally must either file a registration statement containing details about the company and the offering with the SEC (e.g., Form S-1 for IPOs), unless an exemption applies. Failure to comply can lead to rescission rights (where investors can demand their money back), SEC enforcement actions, state securities violations, and damage to your company’s ability to raise future capital.

A. The “Private Placement” Exemptions (Regulation D)

Regulation D provides several exemptions from SEC registration for private securities offerings. Most startups rely on these exemptions to avoid the time and costs of a public offering.

Some exemptions provided in Regulation D depend on whether an investor is an “accredited investor.” Accredited investors are individuals or entities meeting specific criteria relating to their income (more than $200,000 (or $300,000 jointly with a spouse) for the last two years), net worth (more than $1,000,000 excluding a primary home), or professional expertise (e.g., holding certain professional certifications, such as Series 7, Series 65, or Series 82 licenses). The law assumes that if an investor qualifies as an accredited investor, they have the financial sophistication and capital to withstand the high risk of startup investing, and therefore require less regulatory oversight.

The Regulation D exemptions most commonly used by startups are:

Rule 504: For smaller rounds (up to $10 million in a 12-month period) and allows for unlimited accredited and non-accredited investors. However, general solicitation is generally restricted unless specific state law conditions are satisfied.

Rule 506(b): This is the most common exemption, and covers unlimited amounts from an unlimited number of accredited investors and up to 35 non-accredited investors. However, general solicitation is not permitted (unless using specific safe harbors such as certain Rule 148 “demo day” provisions). Other than notice filing requirements, state securities laws (i.e., Blue Sky laws) generally do not apply to Rule 506(b) offerings, but this preemption does not eliminate all state requirements.

Rule 506(c): Allows for general solicitation and advertising, but only covers sales to accredited investors.

Although Regulation D provides an exemption from filing a full SEC registration statement, the company must file a Form D with the SEC within 15 days of the first sale under Regulation D. This form is public and includes information about the company, offering terms, and investor count. In addition to federal Form D filing, you may need to file notice with state securities administrators or pay notice filing fees in states where you’re offering securities.

B. Other Capital Raising Avenues

When raising capital, founders often look beyond traditional private placements to reach a broader audience or the crowd. The following exemptions each offer a different balance of speed, cost, and the ability to accept money from non-accredited investors.

Regulation Crowdfunding (Reg CF): Reg CF allows startups to raise small amounts of capital from the general public (both accredited and non-accredited) through online portals (often called “equity crowdfunding”).

Max Raise: Up to $5 million in any 12-month period.

Investors: Open to everyone, but non-accredited investors are subject to strict investment limits based on their income and net worth.

Requirements: Must be conducted through a single SEC-registered intermediary (a “funding portal” like Republic or Wefunder).

Compliance: Requires filing a Form C with the SEC and submission of financials audited by an independent CPA if raising more than the statutory threshold.

Best For: Early-stage startups with a strong consumer following or community who want to turn their users into shareholders.

Regulation A+: Reg A+ is a hybrid between a private placement and a traditional IPO. It allows companies to raise significant capital from the public with more transparency than a private deal but less “red tape” than the NYSE or NASDAQ.

Max Raise: Divided into two tiers:

Tier 1: Up to $20 million per year (requires state-by-state “Blue Sky” approval).

Tier 2: Up to $75 million per year (pre-empts state laws but requires audited financials and ongoing SEC reporting).

Investors: Open to the general public.

Test the Waters: Founders can gauge interest from the public before spending money on the formal legal filing (Form 1-A).

Best For: Mid-to-late-stage startups or real estate projects looking for a “public-lite” experience.

Section 4(a)(2): Section 4(a)(2) is the foundational “statutory” exemption for private offerings. Most modern private raises actually use Regulation D, which is a “safe harbor” built on top of 4(a)(2), but unlike Regulation D, Section 4(a)(2) does not require a Form D filing, but because there are no safe harbors, it is harder to document compliance.

Max Raise: No dollar limit.

Investors: Limited to a small group of accredited investors. No general solicitation allowed.

Requirements: Very few formal SEC filings compared to Reg CF or Reg A+, but you must ensure every investor has “access to the type of information a registration statement would provide” (usually via a private placement memorandum).

Best For: Traditional “quiet” rounds from VCs, angel groups, or friends and family where you don’t need to market the deal publicly.

C. Compensating Employees (Rule 701)

Rule 701 is a critical safe harbor provided by the SEC. It allows private companies to issue equity (e.g., stock options, restricted stock, or RSUs) to employees, directors, and consultants as compensation without having to go through the expensive process of registering those securities like a public company.

Without Rule 701, most startups would find it legally impossible to offer the “equity upside” that is essential for attracting top-tier talent. However, Rule 701 does not automatically preempt state securities laws, and depending on the jurisdiction, additional state-level exemptions or filings may be required. Additionally, in any 12-month period, the amount of stock a company can issue is capped at the greatest of the following:

$1,000,000 in total value;

15% of the total assets of the company; or

15% of the total outstanding amount of that class of securities (e.g., common stock).

If the aggregate sales price of the securities issued in a 12-month period exceeds $10 million, the company must provide much more detailed disclosures to all recipients, including:

A summary of the material terms of the equity plan.

Risk factors associated with the investment.

Financial statements that are not more than 180 days old. This is often the most difficult requirement for “stealth” startups that want to keep their financial information private.

Section 409A of the Internal Revenue Code governs the requirements for valuation of the stock issued. Under Section 409A, startups are required to set the strike price of employee stock options at or above fair market value to avoid severe tax penalties. If the IRS determines that stock options were granted “in the money” (i.e., below FMV), the penalties fall primarily on the employees or other recipients. All vested options become taxable as income immediately, even if they have not been exercised, with an additional 20% excise tax on the value of the options and any applicable state-level penalties.

Startups can obtain safe harbor status with respect to their valuations (i.e., the IRS will presume that the valuation is reasonable) if one of the following methods is used: (1) hiring an independent third party to perform the valuation, (2) using a person with significant relevant experience to perform the valuation (if the company is less than 10 years old with no public market), or (3) using a consistent, pre-set formula.

D. State Securities Compliance (Blue Sky Laws)

In addition to federal regulations, startups must navigate Blue Sky laws, state-level securities regulations designed to protect investors from fraudulent sales and practices. Under the National Securities Markets Improvement Act (NSMIA), the federal laws preempt most state registration requirements for “covered securities.” This means that if you raise money under Rule 506(b) or 506(c) of Regulation D, states cannot require you to register or qualify your offering. However, states still retain the right to require a notice filing in each state where securities are offered (typically the same Form D filed with the SEC), collect a filing fee (typically $100-500 per state), and require a consent to service of process (allowing them to serve legal papers to the company). In nearly all states, the notice filing is due within 15 calendar days of the first sale to an investor in that specific state.

Non-covered securities (e.g., Rule 504 offerings, equity issued under Rule 701) may require state registration or qualification in each state where they are offered, which is expensive and time-consuming.

Missing a Blue Sky deadline is a common mistake that can have expensive long-term consequences:

Fines and Penalties: Late fees can range from a few hundred to several thousand dollars per state.

Rescission Rights: In extreme cases, failure to comply can give investors the right to rescind their investment, forcing the company to pay them back their full investment plus interest.

Bad Actor Disqualification: Repeated or willful violations could theoretically prevent the company (or its founders) from using certain fundraising exemptions in the future.

Due Diligence Issues: Future investors will check your Blue Sky history. Unfiled notices create a legal mess and result in increased legal fees to clean up before you can close your next round.

Conclusion: A Recap of The Financing Roadmap

Understanding the typical timeline and sequence of fundraising helps you plan effectively. The timeline below is illustrative; some companies raise capital faster or slower based on product traction, market conditions, and investor availability. The key is starting the legal and corporate foundation early so your company can move quickly when an investment opportunity arrives.

Pre-Seed (Months 1-3)

Establish Delaware C corporation with proper certificate and bylaws

Properly document founder equity with vesting and 83(b) elections

Create initial cap table and board structure

Develop initial business plan and pitch deck (12-15 slides)

Begin building core product and early customer interviews

Establish IP protection (IP assignments from founders/advisors)

Seed Round (Months 4-9)

Identify friends, family, and angel investors (target $250K - $1M+)

Choose instrument (convertible notes or SAFEs)

Prepare SAFE or note term sheets with key terms (valuation cap, discount, pro rata rights)

Negotiate terms with lead investors (often with MFN clause for fair treatment)

Ensure securities law compliance (investor questionnaires, Form D filings, state analysis)

Close seed funding in tranches or as a single close

Series A Preparation (Months 10-15)

Build team and initial product; demonstrate traction (users, revenue, engagement)

Refine financial projections based on actual data

Clean up corporate records and cap table

Prepare data room with all diligence materials

Identify potential lead investors via network introductions

Prepare Series A pitch materials (slide deck, business plan, financial model)

Series A Round (Months 16-21)

Target lead investor introduction

Pitch meetings and investor education

Investor diligence process (financial, legal, technical, market)

Term sheet negotiation (valuation, board composition, protective provisions)

Preferred stock documentation (SPA, certificate amendment, voting agreements, etc.)

Board resolution approvals and SEC filings

Due diligence closing items and conditions

Final closing and wire of funds

Fundraising is an often time-consuming process that may distract from running your business. By understanding the distinction between the different financial instruments used to raise money, understanding key deal terms, and preparing meticulously for due diligence ahead of time, you can streamline the process and be positioned for success not just in fundraising, but in building a valuable, sustainable business.

The landscape of startup financing has evolved significantly, and opportunity for founders with great ideas and the discipline to execute properly has never been greater.

Ready to start? Click here to schedule a consultation with Kalaria Law today and navigate the complex journey of raising capital while protecting your legal and financial interests.

Disclaimer: This article is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute formal legal advice.